The paradox of AI in 2025

And how to overcome it

Every few months, a new report lands claiming the same thing: most AI projects fail. Depending on who you ask, anywhere between 60% and 80% of them never make it to production, or never deliver any real value once they do. Entire budgets evaporate into endless pilots, PowerPoints, and “AI strategy” decks.

And yet, at the same time, everyone from researchers to accountants to your aunt’s book club seems to be using ChatGPT or Copilot to get real work done — writing emails, structuring notes, summarising meetings, generating code, even planning holidays. In short: at the personal level, AI is obviously working.

But it’s more than that: the markets are voting with their money. Major-institutions and investors continue to pour money into AI and through that investment they are betting, not just on the technology, but on a future economy powered by it. And every few days, a new report lands claiming to have quantified the impact of generative AI on the economy of tomorrow.

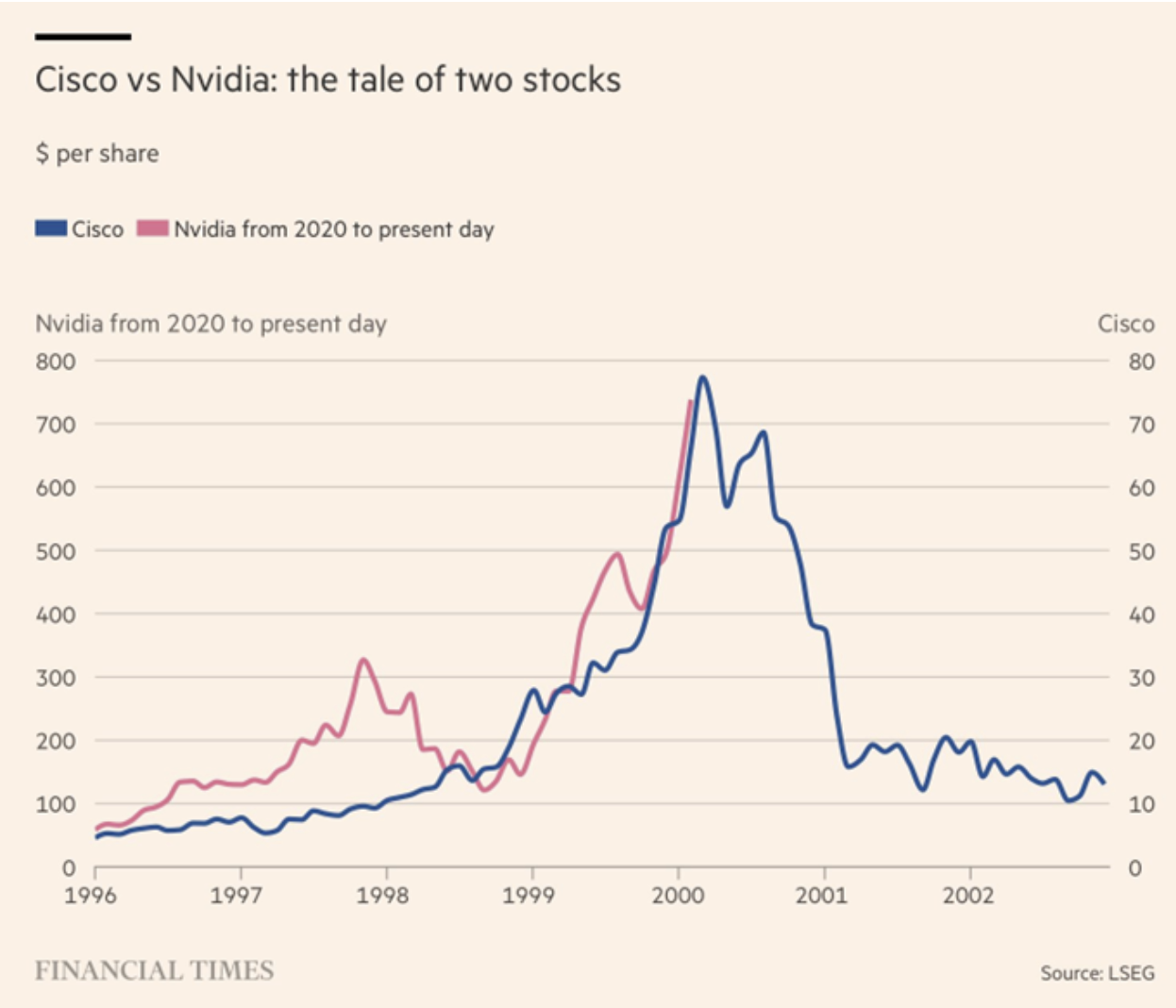

Of course, some of this energy is fuelled by an investment bubble, the kind we’ve seen before. Many are quick to point to the dot-com bubble , when the world economy poured money into ideas that later collapsed. But two decades on, work without the internet is unthinkable for most. Hype doesn’t guarantee value, but it doesn’t preclude it either. The question is not whether AI is overinflated today (it is), but which parts of it will become the infrastructure we rely on tomorrow.

So what’s going on? How can AI be simultaneously the most useful technology of our generation and a graveyard of failed projects?

Welcome to the paradox of AI in 2025.

What’s going on?

At Social Technology Lab, we’re honestly not surprised. There’s a real irony in the current state of AI: its very ability to make advanced capabilities accessible to people without deep technical expertise is exactly what leads to so many failed pilots. Building effective, scalable, and reliable systems with generative AI at the core is an extremely challenging task, for a multitude of reasons. But when you can spin up a chatbot in an afternoon, it’s tempting to believe the problem is solved. “Let’s just put a chatbot on it!” is the new “let’s build an app.”

But AI is much more than just a chatbot: it’s a new way of encoding knowledge and reasoning into everyday tools. Used thoughtfully, it can transform entire workflows, extending human capability and productivity in meaningful ways. And we can interact with that new intelligence in more ways than one. This is what many of the unsuccessful pilots fail to recognise, and in doing so, they set themselves up for failure by skipping the hard but essential work of understanding the workflow, designing the system around it, and figuring out how AI and humans actually need to collaborate.

Successful pilot or crash-landing?

So, what separates the ones that take off and deliver real impact from the ones that end up crash-landing as yet another failed pilot? From our work designing and deploying AI systems, we’ve noticed some patterns. Three, in particular, keep showing up.

To illustrate them, let’s take a look at one of our favourite real-world cases, a project we built with Slachtofferhulp Nederland (SHN), the Dutch organisation that supports victims of crime. Their legal team has to stay up to date on every new court ruling in the Netherlands, hundreds of them each week. Each judgement needs to be assessed on a couple of criteria; they have to answer questions like Was the defendant found guilty? Was compensation awarded? Who was held liable?

For years, doing this meant manually trawling through rechtspraak.nl (the website where all Dutch court rulings are made publicly available), reading page after page to find the few cases that mattered. It was essential work, but painfully inefficient.

We built a system that automatically ingests new rulings each day, analyses them with AI, and highlights key signals. It structures the text, surfaces the important bits, and presents it all in a simple, clean interface. The legal experts remain firmly in control: they decide which cases are relevant, correct AI suggestions, and add reasoning where needed. But how did we design it? Let’s dive into the three principles we’ve discovered along the way.

Human-centred design

Most AI practitioners these days are familiar with the concept of keeping a “human-in-the-loop”. Often, this amounts to adding people at the end, as a glorified safety net for the model’s mistakes. Human-centred design works a bit differently, it starts with putting the humans strengths and experience at the centre. We focus on what humans are already good at and use AI to amplify that, not replace it. With SHN, the starting point wasn’t “how can we automate legal review?” but “what slows experts down, and what could make their judgment go further?”

The tool was built around their workflow: AI does the parsing, structuring, and flagging, but the experts remain the decision-makers. Every element in the UI, from the highlighted text to the confirmation buttons, reinforces that hierarchy.

Controlled Fallibility

In the SHN tool, we expected the AI to make mistakes, and we engineered for them. The system’s job is to help legal experts decide which rulings are relevant, and which are not. To do that, it uses several specialised models that identify passages that indicate the case might not be relevant for SHN. Factors included the absence of a guilty verdict, or absence of a victim in the case. Instead of trying to make these models perfectly accurate, we deliberately tuned them to err on the side of caution.

In this context, we wanted to make sure that no case slipped through the cracks, so we built the models to tend to surfacing more passages for human review. If a relevant passage is found, the reasoning is displayed directly in the dashboard, along with a link that jumps to the exact passage in the original judgment on which the model based its decision. Reviewers can confirm or correct the call in seconds. This shifts the responsibility of the human operator. Before, the human would read through to identify passages and make a judgement. But with AI reading and diligently flagging potentially relevant jurisprudence, the human becomes more of a reviewer.

It’s a high-recall strategy by design: if the system stays quiet, you can be confident everything’s fine; if it rings the alarm, a human double-checks. The mistakes still happen, but they happen out loud; visible, explainable, and reversible. That’s what makes the system trustworthy: transparency builds trust.

Rethinking Interfaces

Working with AI often means rethinking the interface itself. For simple, generic tasks like writing, summarising or answering questions, a one-size-fits-all chatbot works just fine. But when AI becomes part of a specialised workflow, the interface can’t just be a text box. It has to express how the AI and the human collaborate. In the SHN project, that meant building something very different from a chat interface. The legal team doesn’t “talk” to the AI, instead they work with it. The interface shows rulings, structured indicators, and visual cues that make the AI’s reasoning tangible. You don’t ask it questions; you see what it inferred, where it’s uncertain, and what needs confirmation. Every click, every highlight, every filter is tuned to how legal experts think and make decisions.

Designing this kind of workflow requires imagination. You’re designing more than a UI, you’re designing a conversation between human judgment and machine pattern-recognition. The best interfaces don’t hide the AI; they reveal it in just the right way, making collaboration natural instead of mysterious.

Wrapping up

The lesson from all this is that AI succeeds when it’s built around people, not in spite of them. The technology is powerful, but real impact only appears when it’s woven thoughtfully into human workflows and judgment. What we’ve seen across successful projects is that three principles matter most. It starts with human-centred design, grounding the system in the strengths, habits, and decision-making patterns of the people who use it. It requires controlled fallibility, engineering the AI to make its mistakes in the open, in ways that are easy for humans to understand and correct. And it depends on rethinking interfaces, designing tools that make the collaboration between human and machine visible, intuitive, and aligned with the actual workflow.

Most failures come from assuming that AI’s fluent output equals reliable intelligence. The projects that succeed are the ones that respect human expertise, make uncertainty visible, and build interfaces that support a genuine partnership between human judgment and machine pattern-recognition.